The new ‘Conceptual note on short–term climate scenarios’ from the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) is a potentially game-changing step forward. ‘Planet NGFS’ is now beginning to look more like the real world. In shifting from long term to short term scenarios, looking out 3-5 years, it has clearly outlined the practical limitations of its previous long term scenarios.

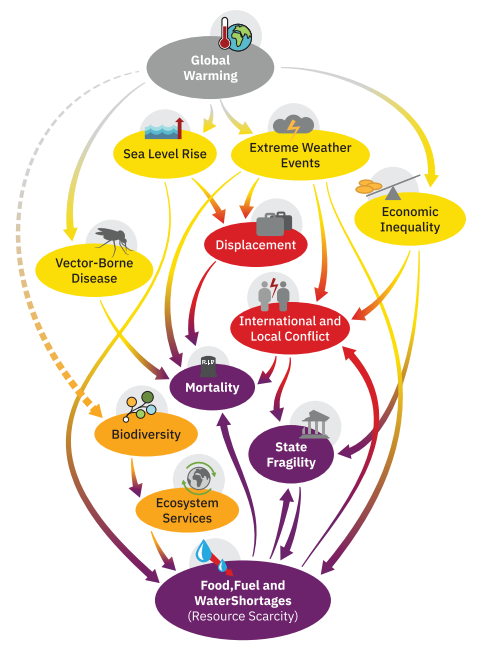

This is much more than a shift in time horizons, it has recognised that:

- different drivers are involved

- chronic physical risk is a ‘predetermined’ over such horizons

- smooth pathways need to be replaced with volatility and non-linearities

- financial market expectations and stress are key

- greater sectoral and geographic granularity will be needed

These are welcome points which the Real World Climate Scenarios (RWCS) Initiative has been emphasising for some time. The new set of NGFS scenarios based on this new thinking are likely to highlight much bigger risks and opportunities than previously suggested. While the NGFS notes that their primary purpose is to integrate climate risks into stress testing and macroeconomic forecasting, this will have profound implications for not just policy but also for financial institutions as they look to develop and implement their transition plans.

But while this a great leap forward towards greater realism in climate scenarios, there is still some way to go, particularly to make them practically useful for financial institutions:

1. Economic growth is not just an impact, it’s a driver

NGFS made a fateful decision when it began developing its long term scenarios to use just one baseline economic growth pathway. Specifically, it uses the IPCC’s Shared Socio-economic Pathway (SSP) 2 , aka “middle of the road”, which assumes that global GDP growth continues smoothly in line broadly with historic trends. Since then the NGFS has effectively ignored the other four IPCC pathways, which have the global economy growing at very different rates, reflecting different economic and political narratives. Thus, while SSP 2 points to gain in global real GDP of 111% by 2050, SSP1 shows a rise of 160%, and SSP3 66%.

So the focus of the NGFS is resolutely on the impact of climate risk on the economy, not the other way around. This is despite the obvious reality that growth has been both a key determinant of emissions and a source of shocks, affecting politics, climate policy, technology and consumer choices. A simple illustration of this the observation that the only year that we have achieved the required reduction in global emissions was 2020, in the midst of the recession triggered by the Covid 19 pandemic.

Short term scenarios should therefore consider a variety of different pathways for GDP. In other words, rather than a climate-economy frame, their scenarios should use an economy-climate-economy frame.

2. The disruptions that lie ahead are still being underestimated.

Decarbonisation implies a whole economy transformation which involves disruptions greater than the NGFS is even now conceding. Although it recognises non-linearities, it is still approaching the analysis with an equilibrium mindset in which ‘shocks’ are largely cyclical disruptions around a trend, rather than potential tipping points for both physical and non-physical systems. Disappointingly, the modelling section of the report makes no mention of non-equilibrium models.

Moreover, the first criterion in its selection of shocks was “they could be modelled within existing climate and economy models”. In other words, rather than realistic narratives driving models, their models are, in part, dictating the narratives.

We are not only hurtling towards several critical climate tipping points, we must contemplate potential political, economic and technological tipping points, both negative and positive.

At one point the NGFS report rightly asserts that ‘the chronology of events is also critical.’ The idea that evolution of systems, including the climate, political and economic systems, is path dependent is a key insight of complexity science that is notably absent from the models that the NGFS discusses. This leads to a blindspot about ongoing structural changes which could take the world further and further away from the past trends (which are enshrined in SSP2).

3. Politics is the elephant in the room

Transition risk dominates four of the five scenario narratives presented in the NGFS report, an important element of which is the trajectory of climate policy. But these narratives are still largely on ‘Planet NGFS’, where climate policy is represented largely by a (shadow) global carbon price, phased in either gradually or suddenly.

The rich real world diversity of policies and cross-country differences are acknowledged but barely addressed. This is hardly surprising, because the bare-knuckle political fight that is taking place nationally and internationally over climate policy is not confronted by the NGFS. Yet the widespread political polarisation over climate, which has already seen some countries not merely delay action, but reverse it, has to be confronted in any realistic set of scenarios. It is worth noting that between now and 2030 we will have 20 elections in ten key countries where election results are not pre-ordained.

The nearest that this report gets to this point is its final scenario, ‘Diverging realities’, which focuses on a broad divergence between the advanced and emerging world as a result of a failure of capital to flow from the former to the latter. This is indeed an important issue, but other obvious questions, not least about the consequential tension between the West and China and/or Russia, and between energy exporting and importing nations, are left unasked. Politics, not policy, deserves to be the key driver of climate scenarios alongside economics.

4. There is still a dubious presumption that the transition will be inflationary

The NGFS report baldly states “transition scenarios are expected to be more inflationary than scenarios involving physical risks”. This predisposition again betrays the NGFS equilibrium thinking and modelling, where the presumption is that policy driven reallocation of resources leads to friction, inefficiency, higher prices, and lower growth. This, perhaps inadvertently, has had the baleful effect of supporting the political backlash against ‘Net Zero’ policies.

Yet Appendix 1 of the NGFS report quotes a Banque de France (BdF) report that raises possibility of a positive productivity shock from green innovation, which would lower prices and raise output. Looking at the evolution of green technologies such as renewable energy, which has plunged in price as it has grown, this possibility needs to be factored much more prominently into the scenarios.

Addressing these points will certainly be challenging. As the NGFS says, this remains an ‘emerging field’. It is to be hoped that academia and business steps up to support the development of more decision-useful scenarios, based on more realistic narratives. The recently published University of Exeter-USS report ‘No Time To Lose’, featured in my previous post, aims to do just that.